The following method call is either something you’re either very familiar with or something you’ve never heard about: ChangeDetectorRef.markForCheck()

If you’ve never heard about it, congratulations! It means you’ve been using Angular in a way that doesn’t require you to mess with change detection, and that’s an excellent thing.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you see that method in many places in your code, your architecture might have a problem. Why is that? As we covered before, there are two types of change detection: Default and onPush.

When we use onPush, we’re telling Angular: “This is a component that relies on @Input values to display its data, so don’t bother re-rendering that component when @Input do not change”.

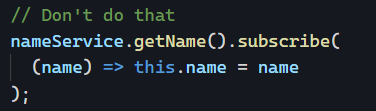

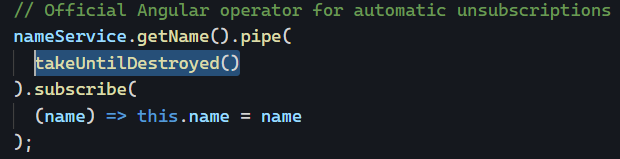

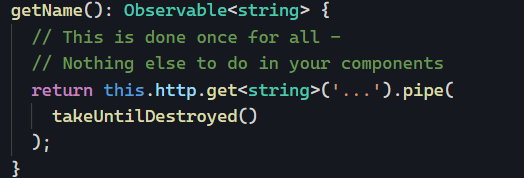

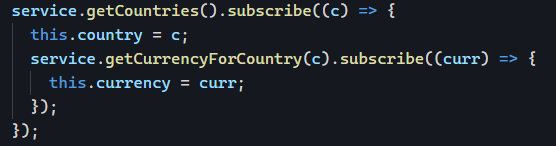

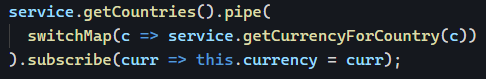

The thing is, sometimes people start using onPush full of good intentions. Then, they start injecting services into their component, and when the data in those services change, the component does not re-render… So, instead of disabling ChangeDetection.OnPush (or figuring out a better way to keep their component as a presentation component), they go to StackOverflow, where people say: Just use ChangeDetectorRef.markForCheck(), and problem solved! Here’s a typical screenshot of such a response:

That’s because ChangeDetectorRef.markForCheck() does exactly that: It’s a way to tell Angular that something changed in our component, so Angular must check and re-render that component as soon as possible. As you can guess, this is meant to be an exception and not the rule.

The main reason why we would use ChangeDetectorRef.markForCheck() is if we integrate a non-Angular friendly 3rd party library that interacts with the DOM and changes values that Angular cannot see because Angular doesn’t manage that DOM. In other scenarios, we should avoid using it and think about a better architecture.